Citizen Scientists Discover Five New Supernovas

More than 40,000 citizen stargazers have helped to classify over 2 million celestial objects and identify five never-before-seen supernovas, in a massive example of citizen science at work.

An amateur astronomy project of cosmic proportions, established by scientists at the Australian National University, asked volunteers to look through images taken by the SkyMapper telescope and search for new objects, with a particular focus on finding new supernovas.

The project was set up using the Zooniverse platform (run by the University of Oxford), which hosts many other citizen science projects, and which was promoted on the BBC2 TV series "Stargazing Live," from March 18 to March 20. [Supernova Photos: Great Images of Star Explosions]

To participate in the project, volunteers signed up online and accessed the Zooniverse platform, which walked them through their tasks.

Zooniverse has hosted many space-related citizen science projects in the past, including hunts for alien planets, "space warp" galaxies and holes in cosmic clouds.

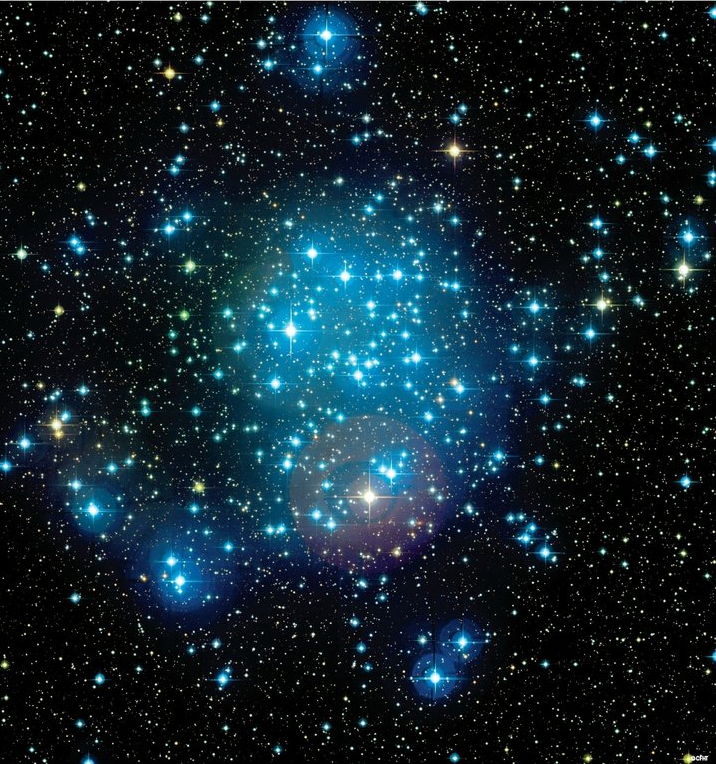

The participants were asked to look at star-filled patches of the night sky, taken by the SkyMapper telescope. The volunteers would look at images of the same region taken at different times, and search for changes that could indicate the presence of different celestial objects.

A supernova, for example, is a large star that has burned up most of its fuel and dies in a great explosion. A supernova eruption can briefly outshine all the light created by all the stars in an entire galaxy — so even a star that is normally too distant to see with a telescope may suddenly become visible if it explodes into a supernova. This means a SkyMapper volunteer might see a point of light appear where there previously was none.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"One volunteer was so determined to find a supernova that he stayed online for 25 hours. Unfortunately, he didn't find one, but he did find an unusual variable star, which we think might explode in the next 700 million years or so," Richard Scalzo, a researcher working with the SkyMapper telescope at the Australian National University (ANU) Research School of Astronomy and Astrophysics, said in a statement from ANU (a variable star is one that changes in brightness when observed from either, either due to changes in the star itself or something between the star and the observer). "It was a huge success. Everyone was really excited to take part."

That excitement paid off, as the project required multiple volunteers. If one of the citizen scientists spotted a possible supernova or some other change in the sky images, then additional volunteers would examine that same region.

If the citizen observers confirmed a new object, then the professional scientists would do a more extensive background check in that region of the sky, Scalzo said in an email. After that, the scientists looked at the object's spectra, a breakdown of the light the object emits. This can tell scientists all kinds of information about the object's makeup and its history.

"Once we have at least one spectrum, we consider what other science we could do," Scalzo said. "Type Ia supernovae can be used to study the expansion history of the universe and dark energy. Other kinds of supernovae can be used, singly or in large groups, to learn more about how different kinds of stars end their lives."

Scalzo said the project required the assistance of so many human helpers because the computer programs need assistance. "Computers are very good at identifying supernova," he said, "but you need a lot of data to train them."

In other words, the scientists have to provide the computer program with lots of examples of what the supernova look like; it isn't as simple as telling the computer to look for changes in the sky images.

"A few years ago, before SkyMapper was ready to take data, another group called the Palomar Transient Factory (PTF) partnered with the Zooniverse to allow volunteers to hunt for supernovae," Scalzo said. "Over a few years, PTF found more than 500 real supernovae with the help of Zooniverse volunteers, and used the data to train a machine-learning algorithm to recognize supernovae more accurately than the volunteers could."

The SkyMapper telescope has only identified 15 supernova, so Scalzo said there is still work to do to improve the programs.

The five newly discovered supernovas have already made their way into a cosmological study of dark energy by the SkyMapper scientists, but Scalzo said there is more work to be done before the results of that study are published. He added that there may be more work for citizen scientists to do with SkyMapper data in the future.

Follow Calla Cofield @callacofield. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Calla Cofield joined Space.com's crew in October 2014. She enjoys writing about black holes, exploding stars, ripples in space-time, science in comic books, and all the mysteries of the cosmos. Prior to joining Space.com Calla worked as a freelance writer, with her work appearing in APS News, Symmetry magazine, Scientific American, Nature News, Physics World, and others. From 2010 to 2014 she was a producer for The Physics Central Podcast. Previously, Calla worked at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City (hands down the best office building ever) and SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory in California. Calla studied physics at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst and is originally from Sandy, Utah. In 2018, Calla left Space.com to join NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory media team where she oversees astronomy, physics, exoplanets and the Cold Atom Lab mission. She has been underground at three of the largest particle accelerators in the world and would really like to know what the heck dark matter is. Contact Calla via: E-Mail – Twitter