Our Universe May Exist in a Multiverse, Cosmic Inflation Discovery Suggests

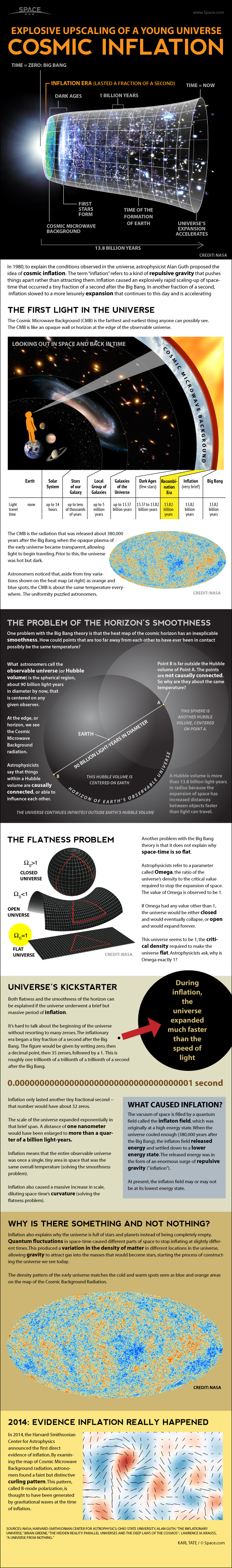

The first direct evidence of cosmic inflation — a period of rapid expansion that occurred a fraction of a second after the Big Bang — also supports the idea that our universe is just one of many out there, some researchers say.

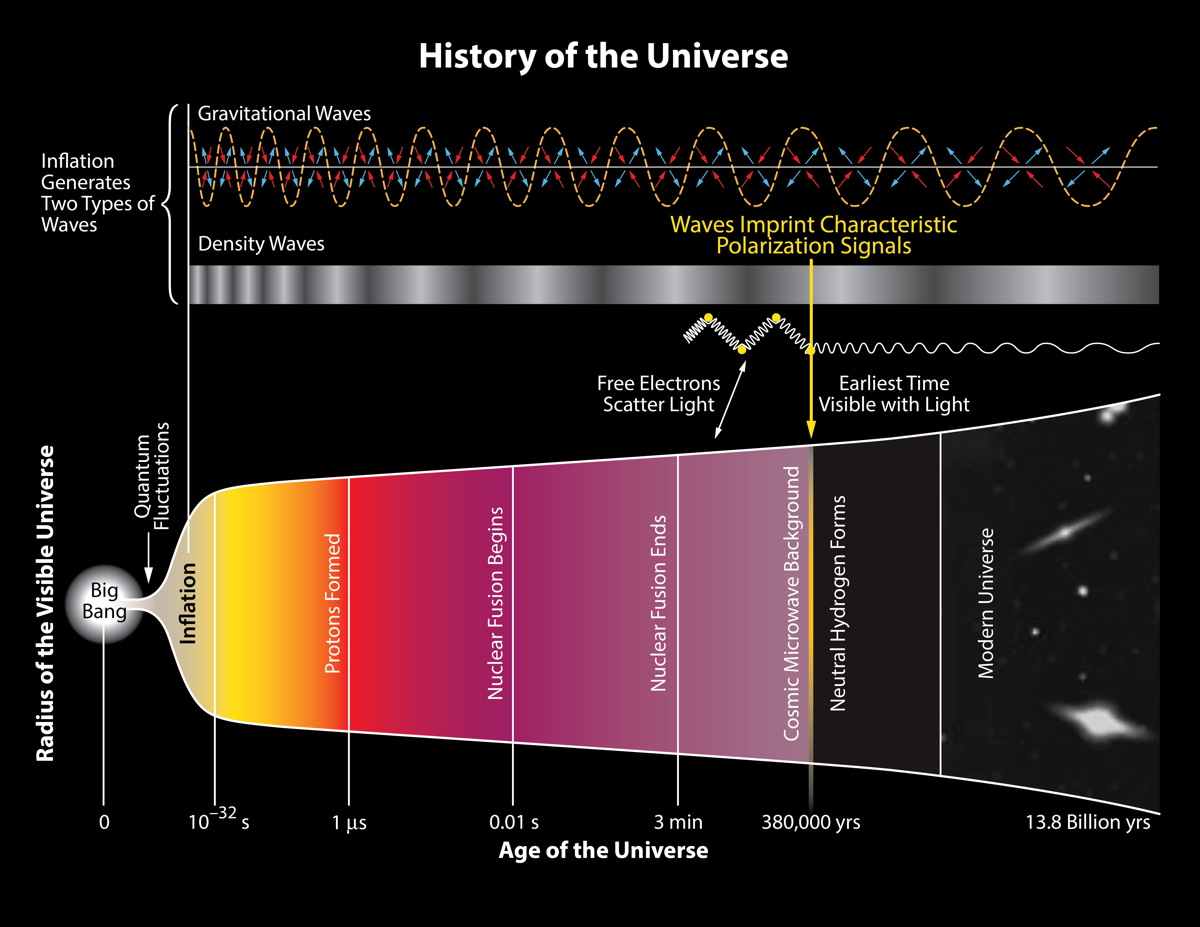

On Monday (March 17), scientists announced new findings that mark the first-ever direct evidence of primordial gravitational waves — ripples in space-time created just after the universe began. If the results are confirmed, they would provide smoking-gun evidence that space-time expanded at many times the speed of light just after the Big Bang 13.8 billion years ago.

The new research also lends credence to the idea of a multiverse. This theory posits that, when the universe grew exponentially in the first tiny fraction of a second after the Big Bang, some parts of space-time expanded more quickly than others. This could have created "bubbles" of space-time that then developed into other universes. The known universe has its own laws of physics, while other universes could have different laws, according to the multiverse concept. [Cosmic Inflation and Gravitational Waves: Complete Coverage]

"It's hard to build models of inflation that don't lead to a multiverse," Alan Guth, an MIT theoretical physicist unaffiliated with the new study, said during a news conference Monday. "It's not impossible, so I think there's still certainly research that needs to be done. But most models of inflation do lead to a multiverse, and evidence for inflation will be pushing us in the direction of taking [the idea of a] multiverse seriously."

Other researchers agreed on the link between inflation and the multiverse.

"In most of the models of inflation, if inflation is there, then the multiverse is there," Stanford University theoretical physicist Andrei Linde, who wasn't involved in the new study, said at the same news conference. "It's possible to invent models of inflation that do not allow [a] multiverse, but it's difficult. Every experiment that brings better credence to inflationary theory brings us much closer to hints that the multiverse is real."

When Guth and his colleagues thought up cosmic inflation more than 30 years ago, scientists thought it was untestable. Today, however, researchers are able to study light left over from the Big Bang called cosmic microwave background radiation (CMB).

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

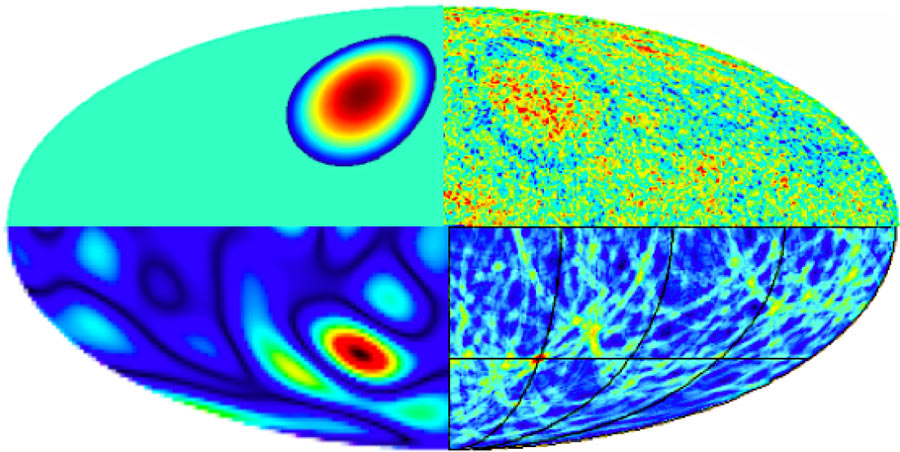

In the new study, a team led by John Kovac of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics found telltale signs of inflation in the microwave background. The researchers discovered a distinct curl in the polarization pattern of the CMB, a sign of gravitational waves created by the rapid expansion of space-time just after the Big Bang.

Linde, one of the main contributers to inflation theory, says that if the known universe is just one bubble, there must be many other bubbles in the cosmic fabric.

"Think about some unstable state," Linde explained. "You are standing on a hill, and you can fall in this direction, you can fall in that direction, and if you're drunk, eventually you must fall. Inflation is instability of our space with respect to its expansion.

"You have something growing exponentially," he added. "If you just let it go … it will continue exponentially growing, so this [the known universe] is one possibility of something going wrong with this instability, which is very, very right for us because it has created all of our space. Now, we know that if anything can go wrong, it will go wrong once and a second time and a third time and into infinity as long as it can go."

Follow Miriam Kramer @mirikramer and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Miriam Kramer joined Space.com as a Staff Writer in December 2012. Since then, she has floated in weightlessness on a zero-gravity flight, felt the pull of 4-Gs in a trainer aircraft and watched rockets soar into space from Florida and Virginia. She also served as Space.com's lead space entertainment reporter, and enjoys all aspects of space news, astronomy and commercial spaceflight. Miriam has also presented space stories during live interviews with Fox News and other TV and radio outlets. She originally hails from Knoxville, Tennessee where she and her family would take trips to dark spots on the outskirts of town to watch meteor showers every year. She loves to travel and one day hopes to see the northern lights in person. Miriam is currently a space reporter with Axios, writing the Axios Space newsletter. You can follow Miriam on Twitter.